To illustrate the concept of stretching a solid along lines of vision, we decided to use a model of a very simple shape: the cube. This allowed us to get a precise view of just how much one can distort something without losing the visual image. The resulting models where quite interesting, especially as none of had been able to imagine how they would look in the end, especially the more complex view.

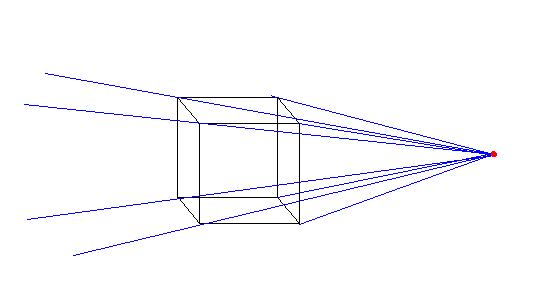

The idea was simple: to project the points of a cube along visual lines of perspective and create another cube from these points:

The cubes themselves were constructed from thin wooden dowels and epoxy.

We made two different distortions: one from a face, the other from a corner.

The first cube is very simple, viewed from one face, slightly above the

plane in which it sits. I ran into problems due to the basic principle

of physics which dictates that no two objects can occupy the same space

at the same time, because we do not live in the world of mathematically

perfect figures and infinitely thin lines. Therefore I decided to simply

mark the vertexes along the lines to represent the distorted cube, and

build the actual model outside of the strings. In the end, this is much

more useful anyway, because it allows one to play with the viewpoint and

shadows.

The second cube was constructed in a similar way, but viewed from a different

direction and so distorted along different lines. This cube rests on its

corner, with the lower of the horizontal corners pointing towards the

focal point. The resulting distortion is very puzzling because it does

not resemble a cube beyond the fact that it has six faces meeting at eight

vertices. It is only symmetrical across one cross-section (vertically

and in the direction away from the viewer). It is especially interesting

to look at in front of a mirror, as one can "see" the perfect

cube close to the eye and yet, in the background, see in the mirror that

it is a completely distorted solid.